Opinion:

Man v Machine – the Ultimate Battle for Safety

Man v Machine – the Ultimate Battle for Safety

Racelogic’s Wesley Hulshof shares his thoughts on the challenges faced by the consumer in understanding driving responsibilities as varying levels of autonomous driving capabilities become more commonplace in vehicles:

For some time now, drivers and non-drivers alike have been excited by the possibility of the fully automated self-driving vehicle. It is one of the big technological leaps anticipated in the 21st century and is expected to save time, countless lives and inevitably the planet. However, are we all getting a little bit overexcited and carried away by the bold claims made by the automotive industry when it comes to Autonomous Driving?

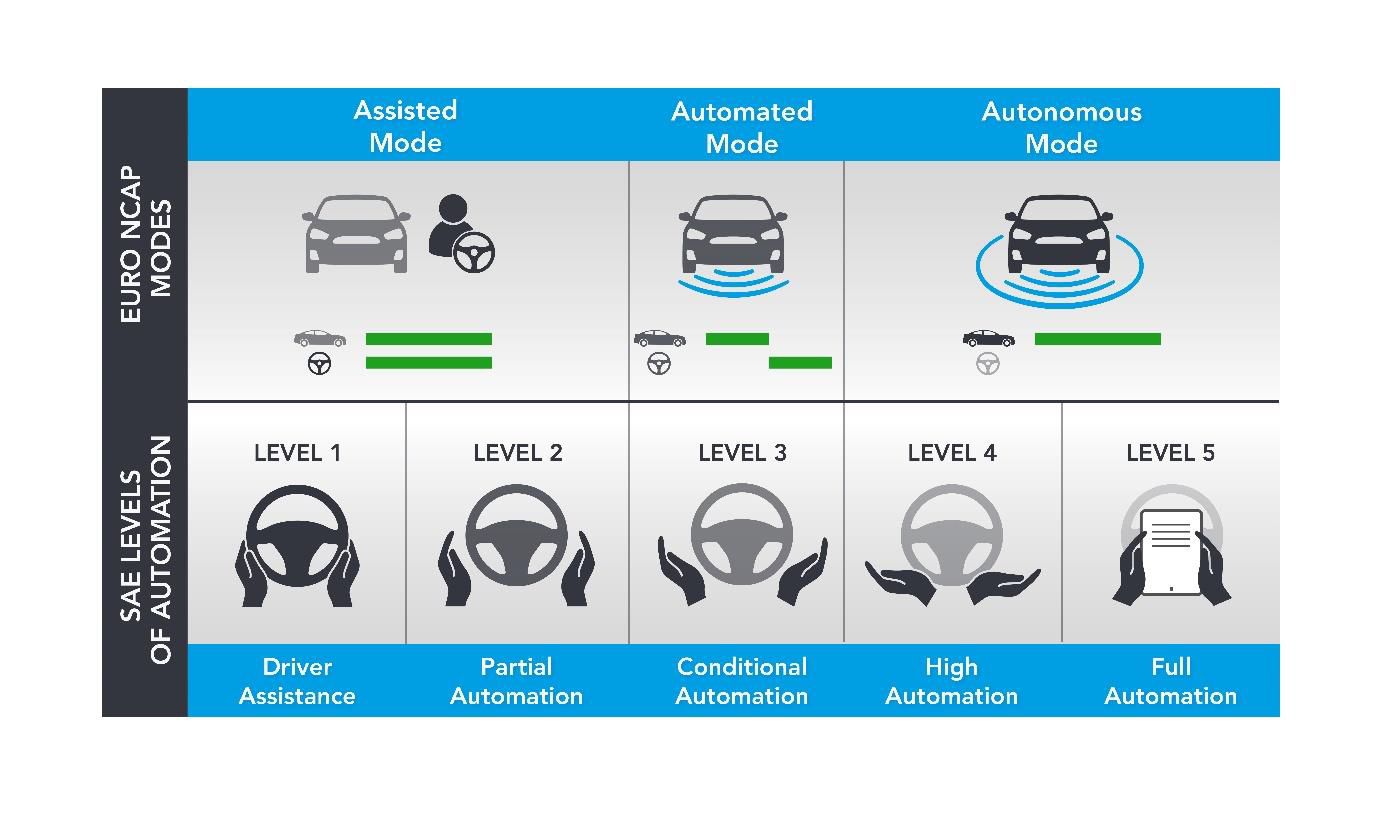

In 2014, the SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) published its Levels of Automation to standardize the conceptual understanding of what building blocks make up ‘full automation’; making better sense of the ‘feet off’, ‘hands off’, ‘eyes off’, ‘brain off’ model. However, has it actually simplified the understanding for the average driver?

I always use my wife as my example when elaborating on this point. She is an intelligent, modern driver who is lucky enough to receive a new high-spec company car every two years. She is guided on what vehicle to choose based on the marketing from each vehicle manufacturer and desire to keep our children safe on the daily drive to school.

Now, it is fair to say that leaning on my years as an active safety test engineer, ADAS technical expert and now principal engineer at Racelogic, I always have my two cents in the negotiation, but inevitably it is up to her to choose the correct vehicle from what she is led to believe from her local dealers. Dealers who are making bold claims based on the global understanding of autonomy and assuring her that “this vehicle is one step away from an autonomous vehicle and therefore the safest place for your family”.

I have even had one dealer try to describe the collision warning/close following triangle on the display as ‘Slip Stream Assist’, completely unaware of the vehicle’s Level 2 ADAS features and misunderstanding the importance of correct communication. Yes, this is a shrewd selling strategy, but dangerously incorrect.

You can see just how there is a disjoint between the technical standards and consumer understanding. It is for this reason that consumer group Euro NCAP are moving away from referring to Level 1-5 but rather 3 ‘modes’ on the basis that people need to understand what exactly their responsibility is, as opposed to referring to the specific SAE Levels which are designed for experts rather than for user communication.

It is true, is it not, that 95% of all accidents occur due to human error?

Using this simplified model, only 3 Levels are important for the user perspective: 1) I am responsible, 2) We are responsible, 3) The vehicle is responsible. But, are these all semantics and in the name of global vehicle safety should we concern ourselves with shared responsibility, or should we just strive for the completely autonomous vehicle? It is true, is it not, that 95% of all accidents occur due to human error?

Well, yes, several studies have cited the human as the final link in the chain that had the potential to avoid the accident, and I myself have been quoted in the press as saying “Remove the Human, Remove the Accident” but this statement, and by extension, I WAS WRONG!

This may seem somewhat counterintuitive, but it all stems from knowledge about the accidents that don’t occur and that missing certain pieces of data may hold more meaning than the data we do have. Let me explain via a famous story:

During World War II, Allies analysed fighter planes returning from battle, which were covered with bullet holes. They looked for correlation between the returning aircrafts, finding the areas that were most commonly hit by enemy fire, and reinforced these commonly damaged areas in an effort to reduce the number of planes shot down. With limited success, the Allies called upon mathematician Abraham Wald, who was asked to study how best to protect aircraft from being shot down. Wald used the idea of survivorship bias to speculate that the Allies had been looking at the situation upside down, perhaps the reason certain areas of the planes weren’t covered in bullet holes was that planes that were shot in those areas simply did not make it back at all. The planes they were looking at were the survivors, the bullet holes they were looking at did not signify the areas that needed reinforcement but rather the areas the plane could be hit and continue to fly and hence were precisely the areas that didn’t need reinforcing.

You cannot measure what isn’t there and by extension infer a conclusion based on only part of the evidence. This is called survivorship bias and explains why I was wrong to make my somewhat simplistic statement all those years ago. In accidentology, we can only measure what does occur and not the accidents we don’t see; we don’t account for the data that doesn’t actually happen. Are we therefore looking at human error completely erroneously, and actually we should be looking at what the human driver did correctly and the frequency of when they did it? In fact, simply replacing the human with a machine would grossly underestimate and undervalue the human’s responsibility within the driving task!

Yes, somewhere around 95% of all recorded accidents have a causation factor cited as the human driver, but the important word there is ‘recorded’. You simply cannot make conclusions based on the recorded accidents, this only shows the individual occurrences where the human didn’t do their job correctly (plus a handful of mechanical defects) and consequently with the human being the only common factor, of course nearly all accidents will therefore be the responsibility of the human themselves, that goes without saying!

Humans are very good at avoiding accidents

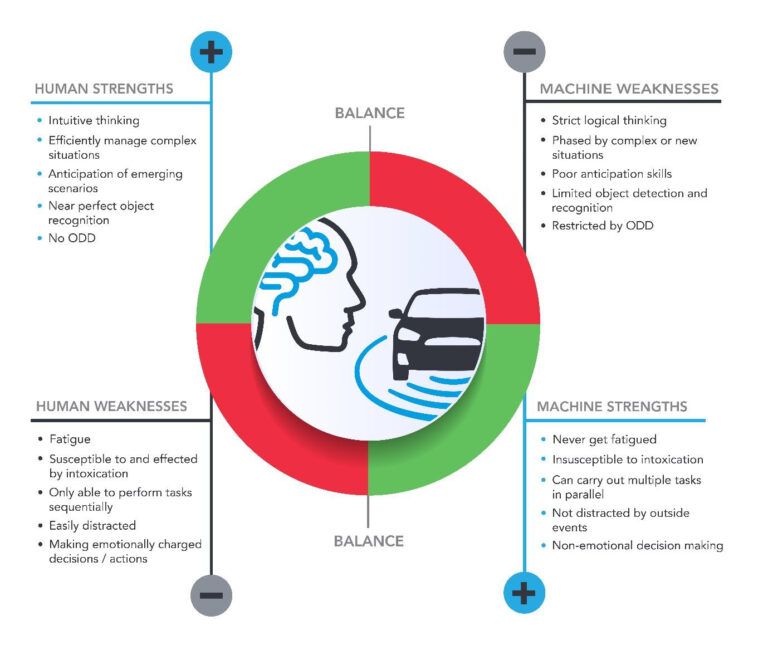

The UK Department for Transport’s main statistical compendium publication ‘Transport Statistics Great Britain’ gives us a good insight into the numbers surrounding road accidents. In 2018, 328 billion vehicle miles were completed on the GB road network, during which 1,784 fatalities were recorded; this means that there were roughly five fatalities per billion vehicle miles (or 183,000,000 vehicle miles between two fatalities). Looking at the data in this backwards way shows that while 1,784 fatalities did needlessly happen; countless potentially fatal accidents did not occur. If you ignore those that can be chalked down to the success of current ADAS systems, the remaining accidents that did not occur only didn’t occur because the human pulled on their experience and dynamic risk assessments that are nearly impossible for self-driving software to replicate. Humans are very good at intuitive thinking and pulling on experience for decision-making, tasks that an algorithm finds very complex. However, the human driver also has many weaknesses, weaknesses that are often seen as the strengths of computer logic, weaknesses such as fatigue, only being able to perform tasks sequentially, or making emotionally charged decisions and actions. One often overlooked benefit is the informal communication happening with every interaction between human drivers, the little nod of the head or the looking into somebody’s eyes to say “I have seen you”; these subjective aspects are not impossible but very complex for a binary, non-subjective model.

It starts to become clear that where the human driver has their strengths, the machine has its weaknesses and vice versa, so only by working off the strengths of both subjects can we really attain the maximum benefit – and this is where we currently are with assisted driving.

You may read this along with other articles and journals and think “well ok then, now I know my responsibilities in the vehicle I can be better than the rest, I know where my responsibilities lie, I will not relinquish control; if nothing else for the safety of myself and passengers”. But you will! You are predetermined to do so; it’s not your fault, the fault of the marketing department or these sorts of articles, it’s just that your brain is wired that way. It is the result of a psychological tendency called habituation.

Habituation is described as ‘the diminishing of an innate response to a frequently repeated stimulus’. It is why that seemingly annoying roadworks outside your office is so frustrating at the beginning of the day but within half an hour you have forgotten about it; the same sound waves have been hitting your ear drum constantly, but your brain has deemed them unimportant enough to reach your awareness. It is why you pick up a smell when you enter a room but over time the smell seems to diminish. Everything, even our innate reflexes, stop working when exposed to the same stimulus again and again.

It explains why even with all the knowledge on accident statistics, and awareness that the human is in fact your best tool to driving a car safely, when in an automated driving mode such as Tesla’s Autopilot, your conscious cognitive effort diminishes from mile 1 to mile 100. You offload increasingly more of the cognitive burden of driving to the ‘Autopilot’ and by mile 1,000 you have relinquished more of your consciousness while driving than you every would have been comfortable with when you undertook that first mile, a mile where you were hovering over the controls like a learner driver not wanting to let go. But, by mile 1,000, your hands are on the wheel and your feet hovering over the pedals, but you are only semi-aware of the situation in front of you, you are close by but in the next room, you are in fact the passenger. You lose those strengths that the human driver has over the machine, those important human responses that avoid hundreds of emerging situations every day, you become… dangerous.

This is indeed backed up by an MIT study which confirmed that Tesla drivers using Autopilot watch the road less and remove their gaze from the road for longer. It concluded that drivers’ attention using Autopilot can, and will, wander.

I believe that merging human and machine strengths and robust and effective handover communication between the two will deliver optimal safety, at least until the time where the machine is at least as clever as the human brain; a brain that has evolved over a billion years, has 540 million years of visual perception data and up to 100 thousand years of data on abstract thought processing. A brain that has somewhere between 100 trillion and 1000 trillion synapses versus the largest current Artificial Neural Network (the building blocks to AI) which has between 1 billion and 10 billion artificial ‘synapses’. So even when sometimes it doesn’t feel like it, the human brain has 10,000 times the computing power of even the best machine. So, what does this mean, should we be wary of automation? Should we just come to terms with the fact that we will always be responsible both legally and morally, will my two young kids ever need to take a driving test?

Only time will tell; just remember that autonomous vehicles cannot remove the risk of driving entirely; they will just reapportion it, and inevitably it seems with all the hype and excitement we will launch fully autonomous cars to the public before they are able to achieve the same strengths as the human driver.